Three Images of Humanity: Body, Library, Continent

Poster for the Paramount Pictures film, directed by Sam Wood and starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, adapted from Ernest Hemingway’s novel by the same name. Hemingway took his title from John Donne’s lines:

Any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

Greetings, readers of my Substack blog, Through a glass, darkly. As I have noted previously, following Libby’s and my illnesses I was moved to reread John Donne’s meditations on his own illness. Donne, a seventeenth century English poet, has always been a favorite poet and essayist for both of us; we love his wit and intelligence, his paradoxes, and his profound probing into issues of love and faith. Last Valentine’s Day I wrote a Substack post in which I discussed Donne’s love poem, The Anniversary. I now turn to his Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions (1624). “Emergent” suggests something arising unexpectedly and calling for prompt action, as in an emergency, a sudden affliction. Donne’s Devotions are brilliant commentaries upon his physical and spiritual condition as he contemplates mortality; they are exemplary models for how we might respond to our own afflictions and approaching death.

It seems to me that since Donne we have lost valuable ways of thinking and experiencing the world; we have an impoverished sense of the fullness and richness of life, and, as a result, are unprepared to face death. This is in part a problem of language. In this essay I will be referring to several closely related terms interchangeably: analogy, metaphor, simile, symbol, image. These examples of figurative language all describe fundamental ways that we make sense of the world: metaphor and simile establish a “this is like that” relationship between disparate things; an image connects one thing to another; an analogy reveals a logical relationship; symbolism allows one thing to represent another. These functions of language provide a coherent and unified experience of the world and each other. Unfortunately, we now live in a modern materialist world of discrete physical objects and beings, with no deep structure to the natural world and no essential characteristics to humanity. We are equally estranged from nature and from ourselves. Donne’s language, however, connects us to one another and to the world. His famous Seventeenth Meditation from the Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions employs three images of humanity: we are each 1) members of a single body; 2) individual chapters or books in a universal library, and 3) not mere islands, but parts of a whole continent. These images connect us analogically, or metaphorically, to concrete, tangible things in the world: our physical bodies, books and libraries, islands and continents. We are like these things; they are part of the same world that we inhabit. Donne’s images of humanity reject the autonomy, isolation, and separation that threaten us all today.

To recapture Donne’s way of thinking and thus to learn from him how to face illness and other life-threatening conditions, we will concentrate on these striking images: how are we like individual members of a larger body? How are we like books and libraries, islands or continents? We will explore each of these distinct but overlapping images of humanity, beginning, in this post, with the body. To establish how natural the language of metaphor is to Donne’s way of thinking here is the opening paragraph of Donne’s Devotions:

Variable, and therefore miserable condition of Man; this minute I was well, and am ill, this minute. I am surprised with a sudden change, and alteration to worse, and can impute it to no cause, nor call it by any name. We study Health, and we deliberate upon our meats, and drink, and air, and exercises, and we hew, and we polish every stone, that goes to that building; and so our Health is a long and a regular work; But in a minute a Canon batters all, overthrows all, demolishes all; a Sickness unprevented for all our diligence, unsuspected for all our curiosity; nay, undeserved, if we consider only disorder, summons us, seizes us, possesses us, destroys us in an instant. O miserable condition of Man.

Nothing has changed since Donne wrote these words! We too make a cult of bodily health: exercise, nutrition, clean air all contribute to building up our bodies into what we hope will be unassailable fortresses. Note the analogical, figurative language that Donne employs: building our bodies through diet and exercise is like constructing a sturdy and solid castle, but, just as that building can be destroyed by canon fire, so too our bodies, in an instant, no matter how sturdy and fit, can fall prey to the sudden emergence of illness and disorder.

Before turning to Donne, however, I would first urge you to listen to the third movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet number 15 in A minor, opus 132, written in thanksgiving for his own recovery from a difficult illness. Titled “Holy song of thanksgiving of a convalescent to the Deity,” it begins with a lovely, peaceful chorale, molto adagio, which alternates with a more energetic andante section labeled “Feeling New Strength.” The whole movement is a beautiful and intimate expression of Beethoven’s thanks to God for recovery from sickness.

Here is a link to the Danish String Quartet’s performance of that movement; their intense Scandinavian demeanor makes me think that all would have been well in the State of Denmark if Hamlet had only formed a string quartet with Horatio, Ophelia, and Laertes:

And now, selected passages from Donne’s Seventeenth Meditation:

The Church is Catholic, universal, so are all her Actions; all that she does belongs to all. When she baptizes a child, that action concerns me; for that child is thereby connected to that body which is my head too, and ingrafted into that body whereof I am a member. And when she buries a man, that action concerns me: all mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated; God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God's hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another. As therefore the bell that rings to a sermon calls not upon the preacher only, but upon the congregation to come, so this bell calls us all.

The bell doth toll for him that thinks it doth; and though it intermit again, yet from that minute that that occasion wrought upon him, he is united to God. Who casts not up his eye to the sun when it rises? but who takes off his eye from a comet when that breaks out? Who bends not his ear to any bell which upon any occasion rings? but who can remove it from that bell which is passing a piece of himself out of this world?

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were: any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind, and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

Donne’s Image of Humanity as a Body

The first image in Donne’s Seventeenth Meditation is that of the body: when the church baptizes a child, Donne says, “that action concerns me; for that child is thereby connected to that body which is my head too, and ingrafted into that body whereof I am a member.” Note that Donne is referring here to two bodies: a body which is also his head, and a body of which he is a member. The first body is the physical Christ, an embodied deity, a God of flesh and blood and bones, who is at the same time the head of both the newly baptized child and Donne himself. The second body, “whereof I am a member,” is also, paradoxically, the spiritual body of Christ, with all its separate members. “Member” here has two senses: members belong to the body of Christ just as individuals belong to an organization, but also analogically as members of a physical body: eye, ear, hand, etc. A child enters the world, not in isolation, but “connected” and “ingrafted” to those bodies: the body of Donne, the body of Christ, and the mystical body of the Church.

The Apostle Paul’s Discourse on the Body

This image draws heavily on several of the Apostle Paul’s letters and his teaching on the body, its members, and its head, as for example, in his first letter to the Corinthians:

For as the body is one, and hath many members, and all the members of that one body, being many, are one body: so also is Christ.

For the body is not one member, but many.

God set the members every one of them in the body, as it hath pleased him. And if they were all one member, where were the body? But now are they many members, yet but one body.

God hath tempered the body together, that there should be no schism in the body; but that the members should have the same care one for another. And whether one member suffer, all the members suffer with it; or one member be honoured, all the members rejoice with it. Now ye are the body of Christ, and members in particular. (I Corinthians 12:12, 14, 18-20, 24-27)

In his epistle to the Romans Paul reiterates his words to the Corinthian church:

For as we have many members in one body, and all members have not the same office; So we, being many, are one body in Christ, and every one members one of another. (Romans 12:4-5)

Paul places these comments on the body in a cosmic context in his letter to the Ephesians:

The God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the father of glory, set Christ at his own right hand in the heavenly places, far above all principality, and power, and might, and dominion, and every name that is named, not only in this world, but also in that which is to come: And hath put all things under his feet, and gave him to be the head over all things to the church, which is his body, the fulness of him that filleth all in all. (Ephesians 1:17-23)

Paul continues a little later in the same letter:

Speaking the truth in love, we may grow up into the Son of God in all things, which is the head, even Christ: From whom the whole body fitly joined together and compacted by that which every joint supplieth, according to the effectual working in the measure of every part, maketh increase of the body unto the edifying of itself in love. (Ephesians 4:15-16)

In his letter to the Colossians Paul develops this understanding of Christ as the Creator of all things. Christ, Paul writes,

is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature: For by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth, visible and invisible, whether they by thrones, or dominions, or principalities, or powers: all things were created by him, and for him: And he is before all things, and by him all things consist. And he is the head of the body, the church; who is the beginning, the first-born from the dead; that in all things he might have the preeminence. (Colossians 1: 15-18)

A little later Paul refers to Christ as

the Head, from which all the body by joints and bands having nourishment ministered, and knit together, increaseth with the increase of God. (Colossians 2:19)

These biblical citations establish a basic principle of unity in diversity for our physical bodies, a unity based upon the ordered relation of our members to each other and to their head, the seat of our consciousness, of our thoughts and intentions. The integral functioning of the body is dependent precisely upon the submission of its members to its head.

Paul appeals to that image of the physical body as the community of Christ’s followers: just as the members of our physical bodies are governed by our heads, so too the individual members of the community constitute a body which is likewise governed by its head, Christ.

With this analogy to the physical body Paul makes his larger claims about human communities. The analogy depends upon the givenness of our bodies, with eyes and ears, limbs and organs. After all, the presence of our bodies to ourselves is a self-evident, lived experience. And the coherent working of our bodily members is self-evidently dependent on their head. It is important to emphasize here that in this analogy Paul is celebrating the physical body and all its members; the body with all its parts is holy. Indeed, Paul writes in I Corinthians,

Know ye not that ye are the temple of God, and that the Spirit of God dwelleth in you? If any man defile the temple of God, him shall God destroy; for the temple of God is holy, which temple ye are. (I Corinthians 3:16-17)

The very idea of the church, the mystery of the church, arises out of this image of the physical body, both male and female, as one flesh, joined in productive unity. The human body is the revelation of the divine; therein lies its dignity, its beauty, its power. Through that analogical relation the body of Christ can be understood as both literal, the flesh and blood of Jesus, and metaphoric, as the community and the bride of Christ.

We Are Members of One Body: Unity in Diversity

However, we are witnesses today to the undoing of that rich analogical correspondence. First, we have lost any sense of the headship of a Creator as a sustaining and governing principle of civic life; there is no unity in the body politic. That language–“body politic”–itself has become alien to us. Instead, we all do as the Israelites did in the time of the judges: “In those days there was no king in Israel, but every man did that which was right in his own eyes” (Judges 17:6). But more drastic still, we have effectively lost a coherent image of our own physical bodies upon which the analogy is based. The human body now consists of individual parts that can be arbitrarily changed and modified; the physical identity of the body has no necessary relationship to the so-called “identity” of the modern self. With that division, the healthy, normal workings of the body are increasingly subjected to technological manipulation. This is true especially of the foundational reproductive capacities of our sexual members, which are routinely interrupted, disturbed, and even destroyed.

Our culture, in abandoning the analogical correspondence between the individual and the communal, between the members and the body, has done violence to the sexual members of our physical bodies in several ways. First, the introduction of contraceptives, particularly birth control pills, was a watershed moment when, for the first time in history, medical technology intervened, not to fight illness or disease, but to disrupt the normal, healthy bodily process of begetting children. Surgical intervention is another category of procedures that goes against the natural reproductive functioning of the body; these includes voluntary tubal ligations, hysterectomies, and vasectomies. Beyond that, we now also have “gender affirming” surgeries which involve the perverse mutilation of healthy bodies: surgeries that cut off the healthy breasts of sixteen-year-old girls and the genitals, both male and female, of teenagers. And, as a gateway procedure normalizing much of this, we have long made routine the horrific surgical abortions of healthy and separate humans gestating in women’s wombs.

We have never been more alienated from our bodies than we are today, though young, eighteen-year-old Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley had a prophetic sense in 1818 of where history was headed. Her Frankenstein is still the definitive fictional account of the dismemberment and desecration of bodies in the name of science and progress. However, a more recent literary example shows how the concrete imagery of the body can be easily abandoned and lost. I am referring to J. B. Priestley’s play, “An Inspector Calls,” first performed in 1945. Near the end of the play Inspector Goole pleads with a group of family members who have been implicated in the death of a young woman, “We are members of one body; we are responsible for each other.” As we have seen, Priestley’s image of the body, of the individual members of society constituting a single body, descends from the writings of John Donne, and finds its ultimate source in the epistles of the Apostle Paul. Priestley is indebted to Paul in his use of this analogy by which the inspector can judge the family. Paul’s account of the body’s members also acknowledged the body’s head, for without it the members are decidedly not responsible for each other. If our culture were to lose the knowledge of these sources then the inspector’s reference could only be to a body without a head.

Paul pictured just such a scene of anarchy and division in his letter to the Corinthians:

If the foot shall say, Because I am not the hand, I am not of the body; is it therefore not of the body? And if the ear shall say, Because I am not the eye, I am not of the body; is it therefore not of the body? If the whole body were an eye, where were the hearing? If the whole were hearing, where were the smelling?

The eye cannot say unto the hand, I have no need of thee; nor again the head to the feet, I have no need of you. (I Corinthians 12:15-17, 21)

Paul argues against such a chaotic dismembering: Christ, by whom and for whom all things were created, has so ordered the members “that there should be no schism in the body.” As Paul says, “he is before all things, and by him all things consist. And he is the head of the body, the church.” This is precisely why Donne can refer to his body as sick: his members are disordered.

In 1945 Priestley’s inspector retained enough knowledge of the past to speak in the language of analogy, and thus affirm the unity of the body with its members. Implicit in that analogy is the acceptance of a specific part of the body: the head. But by 2018, in a television production of the play, that cultural memory had clearly been lost, for the text was crucially changed. No longer did the inspector say, “We are members of one body”; instead, he substituted the phrase “We do not live alone”—a bald, empty claim founded upon nothing. Gone is the body with its diverse members; gone is any understanding of the necessity for a head to provide unity to the body’s diversity; gone is any possible appeal to a higher authority by which the inspector could truly hold the family members responsible for a dead body. Instead, the inspector can only offer an empty abstraction: “We do not live alone.” Thus we witness the contemporary emptying out of what had once been a profound discourse on the body, on its unity and diversity, and on a divine schema that conferred dignity and value upon each individual. We live in the aftermath of that blessed coherence.

The Dismembering of the Body

We also live in the aftermath of October 7, 2023, when Islamists horribly massacred Israeli Jews with unthinkable barbarity. We are still slowly digesting the enormity of those terrifying acts by Hamas, and particularly the desecration of so many young lives. What strikes me as truly evil is the atrocities committed against beautiful young Israeli women: to violate their youthful innocence, their feminine loveliness, and their capacity to bring new life into the world is unspeakably vicious and inhumane. How can we not be tempted to despair?

Yet we are not surprised. Our culture has become hardened to viewing such scenes of violence and cruelty. A generation has grown up with images of children, only a few months short of being born, torn from the womb; they have been taught that the fetus is just a “mass of tissue.” Our young women have learned that there is nothing sacred about virginity or motherhood. So why should we be surprised that students on university campuses across the land are now celebrating and supporting Palestinian men who rape virgins, burn children alive, cut off the heads of infants and the breasts of teen-age girls, and slice open pregnant women’s stomachs to kill little Jewish babies?

And, of course, there is precedent for such acts of dismemberment. To put these appalling deeds in historical context, while also keeping in mind Paul’s discourse on the body, let us consider some ancient scenes of beheadings and dismemberments. These are not just modes of killing; they have a symbolic significance. The severing of a head from a body strikes at the source of the body’s ability to function, rendering useless the physical power of its other members. Beheadings thus symbolize the overthrow of any governing system of power, political or social. Likewise, dividing the body into its constituent parts—arms, legs, hands, feet, head, eyes, ears, etc.—destroys the unity and integrity of the whole. Such a dismemberment represents the breakdown of a collective membership, the dissolution of a community or a nation of its shared values and goals.

We will consider three beheadings recorded in the Scriptures: 1) the I Samuel account of David and Goliath; 2) the story of Judith and Holofernes from the book of Judith, and 3) the Gospel of Mark’s account of John the Baptist and Herod. We will then conclude with two examples of dismemberment: 1) the story of the Levite and his concubine, as recorded in the book of Judges; and 2) the story of Orpheus taken from the classical Roman author Ovid.

David Beheading Goliath (I Samuel 17: 41-51)

The story of David and Goliath, as related in I Samuel, is a classic fulfillment of the biblical promises that God’s people, Israel—small, weak, and outnumbered—will nevertheless triumph over more powerful and stronger enemies. Goliath the Philistine is the very embodiment of physical prowess, an indomitable warrior against whom the Israelites are seemingly defenseless. Yet his disdainful challenge is answered by David’s own confident boast that Goliath’s sword, spear, and shield are powerless against a young man who comes to the battlefield “in the name of the Lord of hosts”:

And when Goliath looked about, and saw David, he disdained him: for he was but a youth, and ruddy, and of a fair countenance. And the Philistine said unto David, Am I a dog, that thou comest to me with staves? And the Philistine cursed David by his gods. And the Philistine said to David, Come to me, and I will give thy flesh unto the fowls of the air, and to the beasts of the field.

Then said David to the Philistine, Thou comest to me with a sword, and with a spear, and with a shield: but I come to thee in the name of the Lord of hosts, the God of the armies of Israel, whom thou hast defied. This day will the Lord deliver thee into mine hand; and I will smite thee, and take thine head from thee; and I will give the carcases of the host of the Philistines this day unto the fowls of the air, and to the wild beasts of the earth; that all the earth may know that there is a God in Israel. And all this assembly shall know that the Lord saveth not with sword and spear: for the battle is the Lord's, and he will give you into our hands.

And it came to pass, when the Philistine arose, and came, and drew nigh to meet David, that David hastened, and ran toward the army to meet the Philistine. And David put his hand in his bag, and took thence a stone, and slang it, and smote the Philistine in his forehead, that the stone sunk into his forehead; and he fell upon his face to the earth.

So David prevailed over the Philistine with a sling and with a stone, and smote the Philistine, and slew him; but there was no sword in the hand of David. Therefore David ran, and stood upon the Philistine, and took his sword, and drew it out of the sheath thereof, and slew him, and cut off his head therewith. And when the Philistines saw their champion was dead, they fled. . . And David took the head of the Philistine, and brought it to Jerusalem; but he put his armour in his tent.

David with the Head of Goliath. Caravaggio (1610)

Caravaggio’s David with the Head of Goliath faithfully renders the contrast between the massive head of Goliath and the slender, delicate features of young David. There is an attitude of resolute determination in David’s face, and perhaps even a grimace of distaste at the unpleasant head he is holding by its hair. David’s eyes look down at Goliath’s head from an elevated position. His left arm is extended away from his own body; it stretches in a straight line from his head to Goliath’s, defining and measuring the physical and spiritual distance between them. Poised and at ease, David holds Goliath’s bloodied sword in his right hand. This is a study in two heads. There is the head of Goliath, ugly, even monstrous, a head that, while living, mocked God’s people and planned their destruction. Now severed from its body, it is powerless to plot evil. Goliath himself, once the head of the Philistine army, is likewise severed from his troops and people. Israel’s enemies have been brought low, their armies vanquished. David’s head, in contrast, is alive with thought as his eyes carefully observe his trophy; his head is fully in command of its lithe young body, the source of its decisive action. Hannah’s prophetic song from earlier in I Samuel has come true:

The bows of the mighty men are broken,

and they that stumbled are girded with strength.

The Lord maketh poor, and maketh rich:

he bringeth low, and lifteth up.

Judith Beheading Holofernes (Judith 13: 4-17)

The story of Judith and Holofernes is another account of a divine deliverance of the Jewish people. This time Israel’s enemy is the Assyrians, and rather than a heroic young man to vanquish the head of the enemy forces, a brave and resourceful young woman named Judith is given that task. The Assyrian general Holofernes attempts to seduce Judith, who arranges things so that she is left alone with him. She gets him drunk and when he is asleep in a drunken stupor she cuts off his head:

All the guests and servants were now gone, and Judith and Holofernes were alone in the tent. Judith stood by Holofernes' bed and prayed silently, O Lord, God Almighty, help me with what I am about to do for the glory of Jerusalem. Now is the time to rescue your chosen people and to help me carry out my plan to destroy the enemies who are threatening us.

Judith went to the bedpost by Holofernes' head and took down his sword. She came closer, seized Holofernes by the hair of his head, and said,

O Lord, God of Israel, give me strength now. Then Judith raised the sword and struck him twice in the neck as hard as she could, chopping off his head. She rolled his body off the bed and took down the mosquito net from the bedposts. Then she came out and gave Holofernes' head to her slave, who put it in the food bag.

Judith has been a popular subject for artists through the ages. I have chosen three paintings that convey well the sense of virtuous resolve in Judith’s triumph over evil. As in the story of David and Goliath, Judith cutting off the head of Holofernes signifies the vanquishing of Israel’s enemies: the “head,” both literally and figuratively, has been severed from the body of Holofernes, and thus also from the body of the forces arrayed against Israel. The paintings by Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi both portray a determined Judith, resolute yet sober in her difficult work. Like David, she finds no pleasure in this act, but proceeds with a calm intensity (Caravaggio) or a matter-of-fact, business-like resignation (Gentileschi). Judith finds the strength to resist evil as she prays to God, “help me carry out my plan to destroy the enemies who are threatening us.”

Judith Beheading Holofernes, Caravaggio (c. 1598–1599)

Judith slaying Holofernes, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1614-18

The painting by Giorgione gives additional depth to the story, showing Judith with her left foot on the now-severed head of Holofernes. Her right hand still holds the sword that slew him. As with Caravaggio’s David, a line can be traced from her head—radiant in its serene beauty—through her graceful and relaxed left arm, down her bare left leg to Holofernes’ head. She has been lifted up, while he has been brought low. In his head, only emptiness; in her head, echoes of her prayer for Israel and of her own brilliant plan, now carried to completion. Judith’s left foot on Holofernes’ head signifies her victory over him, but it also alludes to Genesis 3:15, in which God curses the serpent in the Garden of Eden, and tells him,

And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel. (Genesis 3:15)

Judith, as the seed of Eve, bruises the head of Holofernes, the seed of the serpent. She thus plays her part in the primal opposition between good and evil.

Judith, Giorgione (c. 1505)

John the Baptist, Beheaded by Herod (Mark 6: 17-29)

If the beheadings by David and Judith represent defensive acts against a head of evil, Herod’s beheading of John the Baptist is the very antithesis of those acts. Even though Herod knows that John is a “just man and an holy,” he follows his wife’s desire to deny God’s law. She believes that to sever John’s head from his body will put an end to John’s words; it is a direct effort to silence the law of God, to render John’s prophetic voice mute:

For Herod himself had sent forth and laid hold upon John, and bound him in prison for Herodias' sake, his brother Philip's wife: for he had married her. For John had said unto Herod, It is not lawful for thee to have thy brother's wife. Therefore Herodias had a quarrel against him, and would have killed him; but she could not: For Herod feared John, knowing that he was a just man and an holy, and observed him; and when he heard him, he did many things, and heard him gladly.

And when a convenient day was come, that Herod on his birthday made a supper to his lords, high captains, and chief estates of Galilee; And when the daughter of the said Herodias came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and them that sat with him, the king said unto the damsel, Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt, and I will give it thee. And he sware unto her, Whatsoever thou shalt ask of me, I will give it thee, unto the half of my kingdom. And she went forth, and said unto her mother, What shall I ask? And she said, The head of John the Baptist. And she came in straightway with haste unto the king, and asked, saying, I will that thou give me by and by in a charger the head of John the Baptist.

And the king was exceeding sorry; yet for his oath's sake, and for their sakes which sat with him, he would not reject her. And immediately the king sent an executioner, and commanded his head to be brought: and he went and beheaded him in the prison, And brought his head in a charger, and gave it to the damsel: and the damsel gave it to her mother. And when his disciples heard of it, they came and took up his corpse, and laid it in a tomb.

Caravaggio’s painting of the beheading of John the Baptist shows in the executioner’s face none of the heroism of David and Judith. His face is in shadows and all the other heads in the room are turned downward. There is no exultation at this beheading; only a sordid complicity as five shadowed figures look on. As in the paintings of David and Judith, the beheader’s arm spans the distance from one head to another, but it is only a brute downward force that is at work here. Herodias’ daughter looks on, waiting to receive John’s head in her rounded bowl. There is an erotic, sadistic aspect to this scene, as Oscar Wilde well understood in his play, Salome. This violence against God’s prophet is spiteful, a cruel act of vengeance against his call for sexual restraint, but it arouses the same sexual passions that were on display on October 7, when young Palestinian men ran wild, raping, butchering, burning, in their dark desire to silence Jewish voices and end Jewish lives.

Beheading of John the Baptist, Caravaggio, 1608

Dismemberment of the Levite’s Concubine (Judges 19: 22-30)

The story of the Levite’s concubine in the book of Judges is a difficult, horrific story of sexual violence. This story’s social norms and historic customs are issues best dealt with by biblical scholars; we will focus specifically on the bodily dismemberment of the concubine following her sexual abuse. The vicious gang rape of this woman by men of the tribe of Benjamin, the violation of her body that ultimately resulted in her death, is a disturbing reminder of October 7, when Palestinian men sexually abused scores of Israeli women while in the act of killing them. We witness in this account, as in the reports from Israel, the same perverse desire to degrade and foul the bodies of innocent, defenseless females:

Now as they were making their hearts merry, behold, the men of the city, certain sons of Belial, beset the house round about, and beat at the door, and spake to the master of the house, the old man, saying, Bring forth the man that came into thine house, that we may know him. And the man, the master of the house, went out unto them, and said unto them,

Nay, my brethren, nay, I pray you, do not so wickedly; seeing that this man is come into mine house, do not this folly. Behold, here is my daughter a maiden, and his concubine; them I will bring out now, and humble ye them, and do with them what seemeth good unto you: but unto this man do not so vile a thing.

But the men would not hearken to him: so the man took his concubine, and brought her forth unto them; and they knew her, and abused her all the night until the morning: and when the day began to spring, they let her go. Then came the woman in the dawning of the day, and fell down at the door of the man's house where her lord was, till it was light. And her lord rose up in the morning, and opened the doors of the house, and went out to go his way: and, behold, the woman his concubine was fallen down at the door of the house, and her hands were upon the threshold. And he said unto her, Up, and let us be going. But none answered. Then the man took her up upon an ass, and the man rose up, and gat him unto his place.

And when he was come into his house, he took a knife, and laid hold on his concubine, and divided her, together with her bones, into twelve pieces, and sent her into all the coasts of Israel. And it was so, that all that saw it said, There was no such deed done nor seen from the day that the children of Israel came up out of the land of Egypt unto this day: consider of it, take advice, and speak your minds.

Then all the children of Israel went out, and the congregation was gathered together as one man.

This account would be shocking enough if it were only about the violent gang-rape and killing of the concubine. Gustave Doré’s engraving portrays the immediate aftermath: the dead, sexually mutilated concubine splayed out on a donkey, the Levite raising his hand to the heavens, in apparent supplication for justice. They emerge out of the dark horror of the night’s events into a light that will fully illuminate the evil deed. The Levite’s actions in dividing the concubine’s body into twelve parts and distributing them to each of the twelve tribes of Israel sends a profound, unforgettable message: all of Israel is accountable for her death. We are members of one body. If a body is abused and defiled to the point of death, then its members are no longer unified, no longer functioning together. The Levite’s dispersal of the concubine’s bodily parts throughout Israel is a graphic, physical representation of the fragmentation of a body, and thus also of the moral and spiritual disunity of a nation, of a body politic, when a man could be told to do to a woman “what seemeth good unto you.” The delivery of the twelve parts of the concubine’s body, “together with her bones,” to the twelve tribes aroused the children of Israel out of their moral stupor. They turn in repulsion at this abomination even as today we are sickened by the evil actions of Palestinian men and boys, for whom the sexual degradation and death of Israeli women was a matter of erotic exultation. However, as in the days of the Judges, when Israel “gathered together as one man” in unity, responding to the horror of the concubine’s dispersed bodily members, so too today the nation of Israel, in response to unspeakable brutality, has united as one against Palestinian evil.

The Levite carries his dead concubine away –Gustave Doré, 1890

The death and dismembering of Orpheus

(Ovid, Metamorphoses, from Book 11)

The Greek myth of Orpheus is a fascinating story of an inspired bard, a poet whose enchanting song charmed not only people, but also animals, trees, and even stones. Part of the story is his descent into Hell to retrieve his wife Eurydice from among the dead; Pluto and Proserpine are so entranced by his singing that they allow him to rescue her on the condition that he not look back as he leads her away. In a moment of fear he looks back, and so loses her. He returns to earth, mourning his lost wife and refusing any other love.

In this selection from Ovid’s retelling of the story, jealous women—the maenads of Dionysus—attack Orpheus in a mad frenzy, tearing him limb from limb:

While with his songs, Orpheus, the bard of Thrace,

allured the trees, the savage animals,

and even the insensate rocks, to follow him;

Ciconian matrons, with their raving breasts

concealed in skins of forest animals,

from the summit of a hill observed him there,

attuning love songs to a sounding harp.

One of those women, as her tangled hair

was tossed upon the light breeze shouted, “See!

Here is the poet who has scorned our love!”

Then hurled her spear at the melodious mouth

of great Apollo's bard: but the spear's point,

trailing in flight a garland of fresh leaves,

made but a harmless bruise and wounded not.The weapon of another was a stone,

which in the very air was overpowered

by the true harmony of his voice and lyre,

and so disabled lay before his feet,

as asking pardon for that vain attempt.The madness of such warfare then increased.

All moderation is entirely lost,

and a wild Fury overcomes the right.—

although their weapons would have lost all force,

subjected to the power of Orpheus' harp,

the clamorous discord of their boxwood pipes,

the blaring of their horns, their tambourines

and clapping hands and Bacchanalian yells,

with hideous discords drowned his voice and harp.—

at last the stones that heard his song no more

fell crimson with the Thracian poet's blood.the savage mob hastened to destroy the harmless bard,

devoted Orpheus; and with impious hate,

murdered him, while his out-stretched hands implored

their mercy—the first and only time his voice

had no persuasion. O great Jupiter!

Through those same lips which had controlled the rocks

and which had overcome ferocious beasts,

his life breathed forth, departed in the air.His torn limbs

were scattered in strange places. Hebrus then

received his head and harp—and, wonderful!

While his loved harp was floating down the stream,

it mourned for him beyond my power to tell.

His tongue though lifeless, uttered a mournful sound

and mournfully the river's banks replied.

The language describing the Maenads can be accurately applied also to the rampage of the Arab men on October 7: “the madness of their warfare, … the wild Fury of a savage mob.” There is also a clear contrast between the entrancing beauty of Orpheus’ music, “the true harmony of his voice and lyre,” and the demonic cacophony of the Maenads, “the clamorous discord of their boxwood pipes, the blaring of their horns, their tambourines and clapping hands and Bacchanalian yells, with hideous discords.” The Arab attacks at the Re’im and Nova music festivals in Israel were grotesque reenactments of this scene: the music of love, and peace, and life, interrupted and destroyed in savage abandonment by forces that bring only ugliness and death.

Orpheus is not only killed by the women, his body is desecrated and abused, ripped apart in a frenzy, limb from limb. Ovid notes that “His torn limbs were scattered in strange places. The river Hebrus then received his head and harp.” Like the Israelite concubine, Orpheus suffers a dismemberment; like John the Baptist, Orpheus suffers a beheading. These twin violations done to the integrity of the body coalesce in the image of Orpheus both dismembered and beheaded, his bodily members “scattered in strange places,” his head floating down the Hebrus.

We can apply the Latin term, disjecta membra, to these “scattered members” of Orpheus’ body. The phrase is also translated as scattered fragments, limbs, or remains. And, following the Roman lyric poet Horace, we can refer more specifically to the disiecti membra poetae, the “limbs of a dismembered poet.” Indeed, Orpheus’ body has been torn apart, broken, strewn, and dispersed. And yet, despite this tragic image of loss, there is also a hint that the torn limbs of the poet might be gathered together and reassembled, re-collected, limb by limb, from their scattered resting places. For the phrase can also refer to a poet’s body of work; if the pages or leaves of that work have been scattered to the winds, there is nevertheless the possibility of bringing them back together in a coherent unity. This, as we shall see in a subsequent post, is Donne’s own hope as expressed through his second image: the hand of God binding up “all our scattered leaves again for that library where every book shall lie open to one another.”

In the following two paintings, however, we have only the image of Orpheus’ detached head. John William Waterhouse’s water nymphs look on in somber wonderment at Orpheus’ head, floating in the water beside his lyre. Gustave Moreau’s Thracian maiden has apparently retrieved Orpheus’ head from the river and gently and respectfully carries it on his lyre. There is a palpable sense of loss here: the head, bereft of its body, is powerless to sing; the body, powerless to pluck the lyre. These paintings are bidding farewell to a lost age of poetry and heroism. This, for the Greeks, represents the day the music died.

John William Waterhouse, Nymphs Finding the Head of Orpheus, 1900

Gustave Moreau, Thracian Girl Carrying the Head of Orpheus on His Lyre (1865)

Ezekiel’s Valley of Dry Bones (Ezekiel 37: 1-14)

I will end with Ezekiel’s prophecy of the dry bones. It feels very much like we are now not only living in the Psalmist’s valley of the shadow of death, but also in Ezekiel’s valley of dry bones. Ezekiel asks a question of profound import: where there is death and dismemberment—Sderot—, where bodies have been burned—Nir Oz—, stripped of their flesh—Kfar Aza—, and reduced to bare brittle bones—Be'eri—, the urgent question arises, can these bones live?

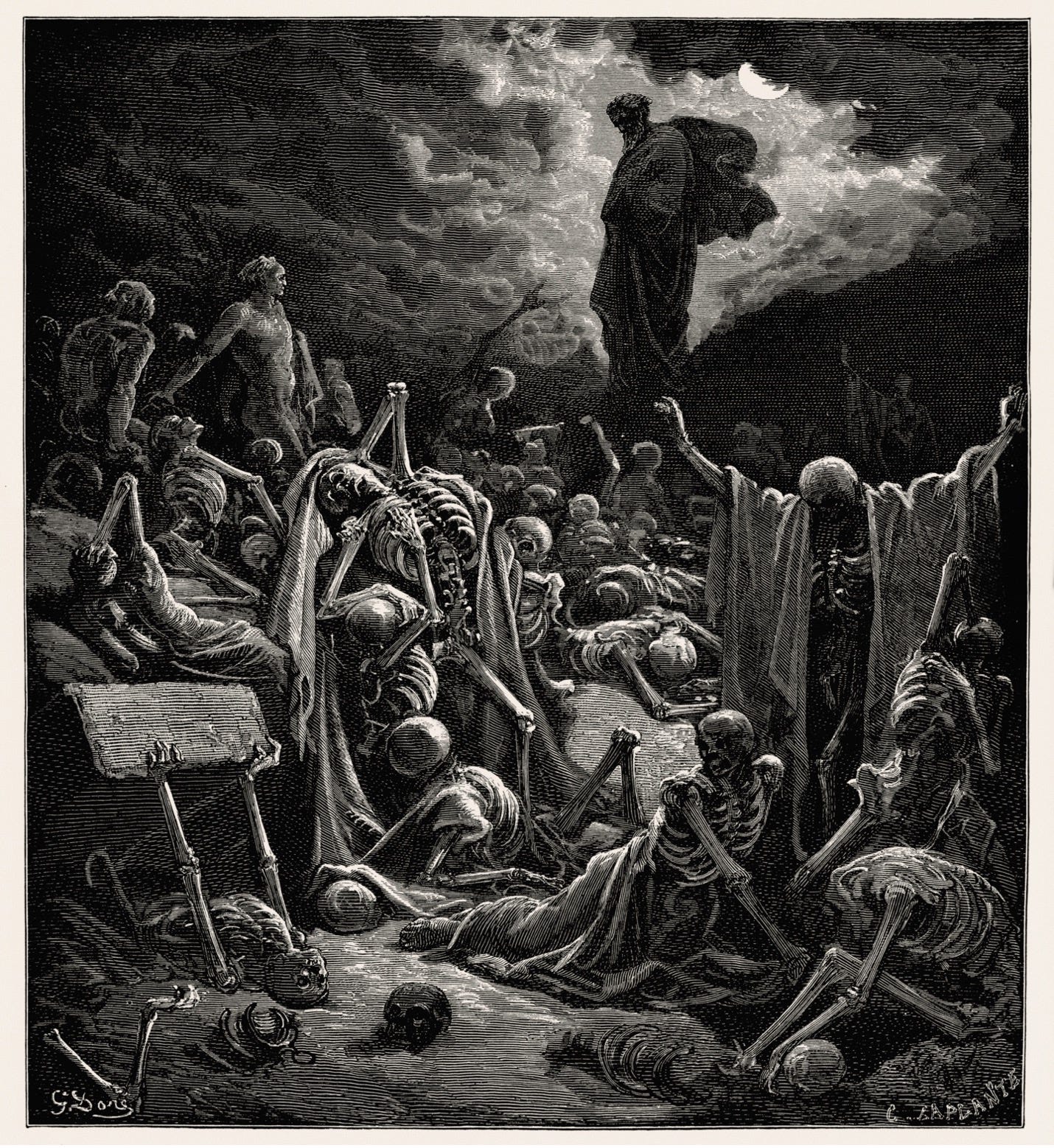

"The Vision of The Valley of The Dry Bones" by Gustave Doré (1866)

Doré’s engraving graphically portrays Ezekiel brooding over the wretched state of the dead, of bodies reduced to skeletons. And into that dry ravaged valley, clamoring with the despair and lost hope of the dead, he proclaims a powerful vision of new life:

The hand of the Lord was upon me, and carried me out in the spirit of the Lord, and set me down in the midst of the valley which was full of bones, And caused me to pass by them round about: and, behold, there were very many in the open valley; and, lo, they were very dry. And he said unto me, Son of man, can these bones live? And I answered, O Lord God, thou knowest. Again he said unto me, Prophesy upon these bones, and say unto them, O ye dry bones, hear the word of the Lord.

Thus saith the Lord God unto these bones; Behold, I will cause breath to enter into you, and ye shall live: And I will lay sinews upon you, and will bring up flesh upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and ye shall live; and ye shall know that I am the Lord.

So I prophesied as I was commanded: and as I prophesied, there was a noise, and behold a shaking, and the bones came together, bone to his bone. And when I beheld, lo, the sinews and the flesh came up upon them, and the skin covered them above: but there was no breath in them.

Then said he unto me, Prophesy unto the wind, prophesy, son of man, and say to the wind, Thus saith the Lord God; Come from the four winds, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live. So I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.

Then he said unto me, Son of man, these bones are the whole house of Israel: behold, they say, Our bones are dried, and our hope is lost: we are cut off from our parts. Therefore prophesy and say unto them, Thus saith the Lord God; Behold, O my people, I will open your graves, and cause you to come up out of your graves, and bring you into the land of Israel. And ye shall know that I am the Lord, when I have opened your graves, O my people, and brought you up out of your graves, And shall put my spirit in you, and ye shall live, and I shall place you in your own land: then shall ye know that I the Lord have spoken it, and performed it, saith the Lord.

May Israel find in these words from Ezekiel assurance and strength to persevere and triumph over her enemies, to restore peace and righteousness to the land. And may all the members of the body—bones, sinews, flesh, and skin—be reunited into a living, breathing whole: not only the individual bodies slain on October 7, but the entire nation, the body politic, of Israel.